There are a lot of Bomber Command books about at the moment. I’ve said this before in previous reviews and ramblings. Every second book in my reading and review schedule (“schedule” suggests order and discipline but there is very little of both!) is Bomber Command to the core. This is great, and not before time, but I’ve discovered I can burn out on a seemingly never-ending diet of Lancasters, Halifaxes and Stirlings. Sacrilege? Perhaps. Shooting myself in the foot? Probably, but my passion ranges far and wide and, as many of you know, has a particular liking for the lesser known theatres and actions. That said, put a Bomber Command book in my hand and I am happy. Give it a twist and I am hooked. Mosquito Down! did just that.

Frank Dell was the youngest of four children. His father had served as a mechanic in the Royal Flying Corps during W.W.I after being deemed too old to fly. He was badly injured by a spinning propeller but returned to the service as an engineering officer and was sent to Canada, and then to the US, with a team to set up training facilities for RFC pilots. His son would follow in his footsteps to some extent.

The Depression had a significant and familiar bearing on the Dell family. Two of Frank’s siblings were considerably older and had left home while the third was born with Down’s Syndrome. Social propriety was a lot different to today and disabilities were very much regarded as an embarrassment more than anything else. Both of Frank’s parents worked hard and the author provides a refreshingly open account of the extent of their love and care. As the youngest he lived at home during the Depression period and was privy to the pressures his father prevailed against, to keep the family furniture business afloat, and the hard times other families experienced. This understanding of the challenges faced by the average person led to Frank being a well-read and informed young man when Britain went to war.

He finished school at the end of 1940 and joined the RAF by way of a one-year university course that was advertised for those wanting a “long-term RAF career”. Quite optimistic for that stage of the war! Delayed by a stay in hospital at the end of his course, Frank was then sent to the US after soloing on Tiger Moths in less than 10 hours.

After being indoctrinated with the ways of the USAAF in Georgia, Frank completed his flying training at various airfields in Alabama. He was selected to fly as an instructor so remained in the States until November 1943. His thoughts on the USAAF ways of doing things, and Stateside life in general, make for interesting, albeit somewhat brief, reading. Of particular interest is his mention of the infrastructure built across the US to enable airliners to navigate by radio beams. He became very familiar with this system and the practice of ‘riding the range’. It was experience that would stand in him in good stead when he finally flew on operations.

Frank had his mind set on flying Mosquitos. With almost 1,000 flying hours under his belt he could choose what he wanted to do. His experiences watching the Battle of Britain had him preferring a defensive role so, being a switched on and observant type who was aware of the loss rates among the bomber force, he volunteered for night fighters. It was not until after the Normandy invasion, his training complete but no night fighter unit posting forthcoming, that Frank was interviewed by Hamish Mahaddie, selection officer for 8 Group Pathfinders, for a possible role flying PFF Mossies. His beam riding skills notwithstanding, Mahaddie said he was ideal for the Light Night Striking Force and would have to complete 45 ops before being considered for the Pathfinders. The LNSF Mossies, which carried 4,000-pound ‘Cookie’ blast bombs, were part of 8 Group anyway. It was the chance Frank needed to fly Mosquitos and he didn’t need to be asked twice.

He took to the Mosquito well and fell in love with it easily. Frank teamed up with his navigator, Ron Naiff, and was posted to No. 692 Squadron at the end of August 1944. Ron had already completed a tour on Stirlings but the LNSF ops could not have been any more different. Trips were flown at high altitude and were rarely more than four hours long, due to the speed of the Mossie, so by mid-October the Dell crew had already completed 12 ops. They were shot down on number 13 … on Friday, October 13.

The target had been Berlin but they never made it. Frank was ejected from the disintegrating aircraft but would not discover the fate of his friend Ron for quite some time. Parachuting on to German soil, Dell struck out for Holland to the west. After a week of sleeping rough, walking at night and an incredible number of close calls with German soldiers and civilians when, surely, the dark nights and bad weather hid his condition and identifying traits, he was discovered sleeping in a barn, in Aalten, Holland, a bare five miles from the German frontier.

What follows makes up the bulk of the book. Frank is moved around several farming families and is integrated, after much vetting, into the local Resistance. The author goes to great pains to describe, in his typical observant style, his Dutch friends and the conditions in which they lived during the occupation of their country. The impact on his life, and the friendships he made, was perhaps greater than his time in the RAF. It was six months of living on the edge, under the noses of a cruel and desperate regime, but among a hospitable and determined people.

Finally liberated shortly after the crossing of the Rhine, Frank, after the requisite leave, volunteered for transport work in India. He returned after six months and, with no progress on an application for a permanent commission, left the RAF to join BEA in 1946. He retired from British Airways in 1976 and remained active in the marvelous Escaping Society until it closed down in 1995.

The main focus of this book is, naturally, the author’s remarkable journey as an evader in Germany and Occupied Holland. Do not expect great insight into the life of a Light Night Striking Force crew. That said, the final op and a beautifully detailed account of the first operation are written about in depth (and are the only ops recounted). The account of the first op covers every aspect of the entire process and, from what I can see, leaves next to nothing out. This could easily have been a wordy list of “then I did this before doing that” but, such is the author’s ability to easily convey his experience, coupled with his observant nature, that the reader is completely absorbed from “ops on tonight” to crashing into bed post debrief. It is business-like and matter of fact but cleverly written with the heart and mind of a lifelong flyer.

Speaking of fine chapters, and backtracking a little, Chapter Seven is a very good, concise discussion of the air war, and its technological developments by both sides, as it pertained to Bomber Command. The author does not get bogged down in detail but manages, in a mere seven pages, to succinctly set the scene for his operational career. It is necessarily short, and could have been so very much longer, but few could have done it better.

The author’s time with the Dutch Resistance is, however, what this book should be known for. While he was not involved in blowing up bridges or other ‘Boy’s Own’ activities, thankfully, Frank was completely immersed in the day-to-day life of the local ‘cell’ and, once again coming back to his skill for observation and interpretation, the recording of this life is one of the more important and valuable accounts I have come across. It is on par with David and Sydney Smith’s tale of The Comete Line in Lifting The Silence. Happily, the book, through its photo sections, is able to give faces to the names of Frank’s many brave Dutch friends. He kept in touch with some of them after the war and their post-war lives and fates, along with other ‘characters’ featured (like Ron Naiff), are given the space they deserve in one of the final chapters. They were extraordinary men and women who melted away and, for most, simply became another face in the crowd. Frank Dell has honoured their memory in no small way.

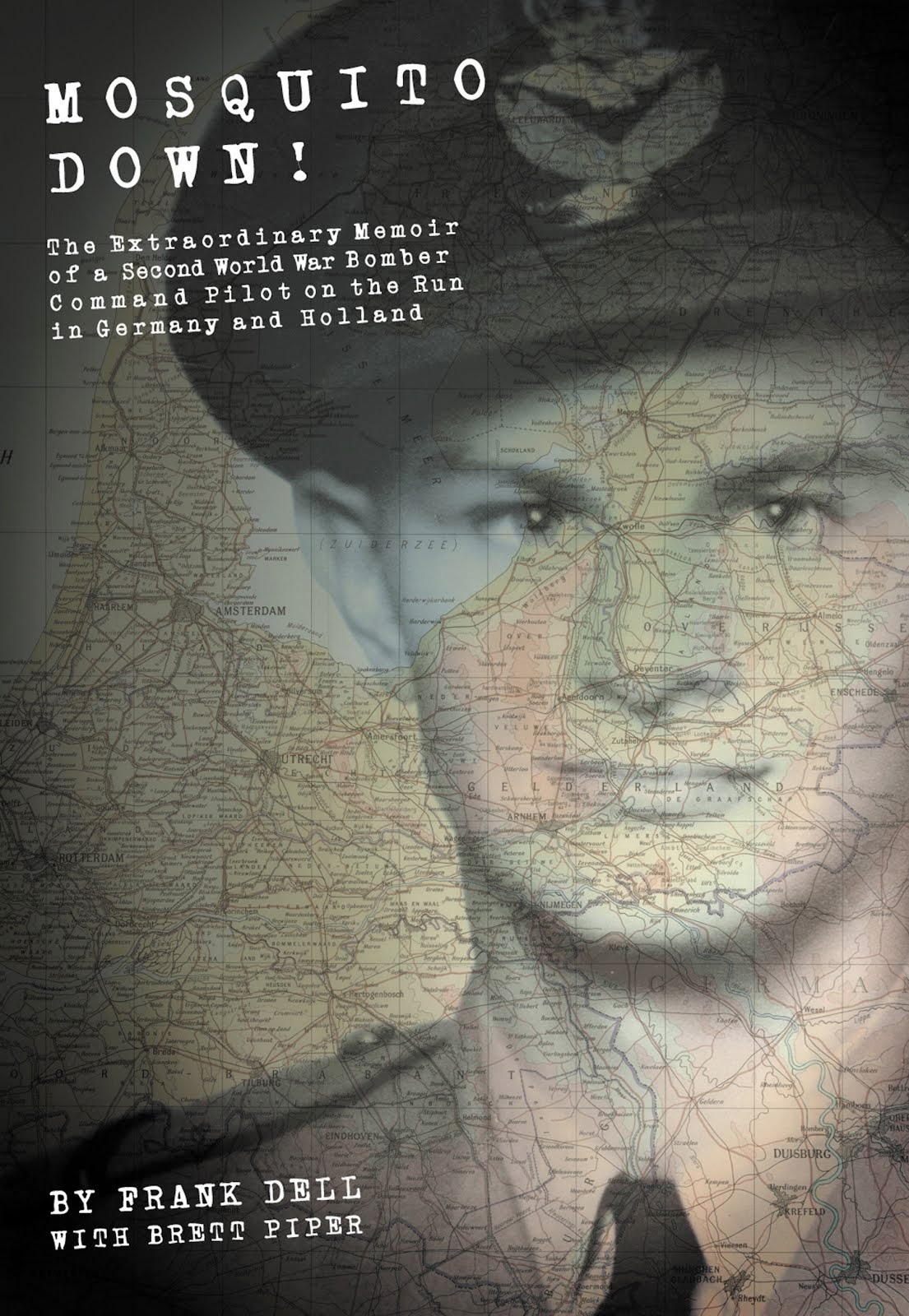

Dell wrote MD! “with Brett Piper”. The latter’s influence is unknown but between them they have produced a book that sneaks up on you. I was not expecting the expressive and open account of hiding in Holland. The cover is understated but if you look carefully you will see the map is the area of Germany and Holland in which the author had his adventures. The story is all there in his face and that map. As expected, this is a well-designed and produced book although the angled text on the cover continues on the front and back flap and, in the confines of said columns, looks a bit odd. It’s the first time I’ve had cause to stop and question a design aspect of a Fighting High book.

I cannot, however, and will not, fault the content. Yes, this is Frank Dell’s wartime memoir but it could just as easily have been called “My Life with the Dutch Resistance” such is the breadth of his account and the honesty with which he tells it. While not a huge book, at 169 pages of main body text, it punches above its weight and presents a much-needed tribute to the men and women of the Dutch Resistance. Perhaps, like has happened with Bomber Command, more can be done to bring their service the wider acclaim it deserves. Mosquito Down! has achieved this through the memories and respect of an old flyer who owes his life to them.

ISBN 978-0992620721